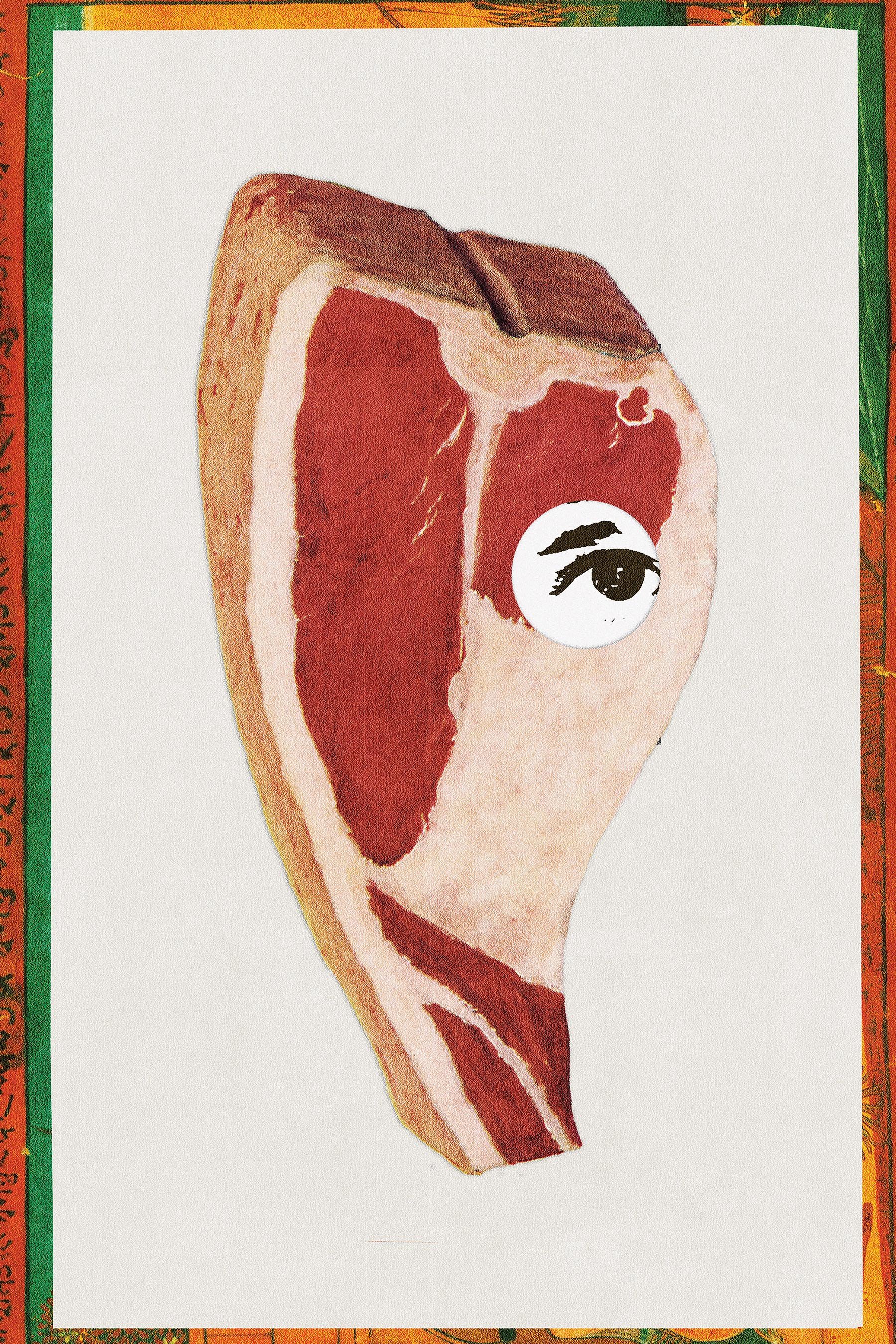

What Good Is Beef

By Siddhartha Deb

Illustrations by Arsh Raziuddin

Produced in partnership with the Food & Environment Reporting Network

At the age of twelve, I parted ways with my religion. All it took was a sandwich.

I broke the news to my father in the evening. He had just come home, early for a man who often stayed at work until 8 p.m., and he was reading the newspaper in a leisurely manner. “From this day forward, I am no longer a Hindu,” I said. It seemed like an important moment, and I spoke with some formality.

“Why?” my father said, not taking his eyes off the Assam Tribune, its pages filled with reports of floods, corrupt politicians, and ethnic conflicts.

“I ate beef at school today,” I said. “It was a sandwich, and it was really tasty,” I added for clarification. Then I waited.

I’m not entirely sure what I was expecting, but perhaps some expression of the violent, conservative family values that lurked just beneath the surface of our lives, in the stories we heard about real people and the imaginary ones we saw in the cinema. Lovers cut adrift for marrying outside of their caste, religion, or simply for choosing their own partner. Newlywed brides mysteriously dead after a disagreement on the dowry amount. The endlessly claustrophobic self-satisfaction of differentiating oneself from others who did not look the same, or worship the same, or eat the same.

But powerful though this attitude was, it came laced with an unusual complexity in Shillong, the small hill town in northeastern India where I was growing up. We might have been in India, in theory a secular nation and in practice often Hindu and Hindi majoritarian, but most of the people around us were Khasis, an Indigenous tribe converted to Christianity by colonial missionaries in the 19th century. They were Westernized, church-going people, the most dominant and powerful of the three tribes that constituted the indigenous population of the state of Meghalaya, of which Shillong was the beautiful, if periodically violent, capital.

My family were the outsiders, my father a Bengali-speaking Hindu refugee from the Partition of 1947 that had placed his home in the new nation of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and led him to settle in the hills of the northeast. But both groups, Indigenous as well as refugee settlers, were far removed from the northern, Hindi-speaking heartland, known there only through the bureaucrats and military officials who arrived from Delhi with unerring self-belief to carry out development work while quashing ethnic unrest.

My father didn’t seem to be a believer in much of anything other than work, science, and a loose version of Gandhian ethics. He had started out as a veterinarian for the government and risen through the ranks to become a senior official in the same department. But unlike the fathers I knew, he washed his own clothes and sewed the buttons back on his shirts when they fell off. When the gutter in our neighborhood silted over, he didn’t wait for municipal workers to show up. To the great discomfort of our neighbors, who liked to remind him that he was a bureaucrat, someone with a phone and a car, he cleaned it himself, with spade and hands. I had never seen him pray and he had never suggested to my sister and me that we believe in god or gods, Hinduism, or caste. When he looked back at Partition, he did not blame Muslims but Hindus with their ideas of otherness and pollution.

But he did not eat beef, and neither did my more religiously observant mother, and in this they were cut off from the immediate environment around them, where it was a normal part of the diet. Eating a beef sandwich at school, with the full awareness that I was breaking a central tenet of the Hindu faith—and against the protestations and reminders of the Khasi classmate whose sandwich I had wolfed down—was a moment of reckoning, surely, even for him. Perhaps he would threaten to disown me, give me a beating, or throw me out of the house. Maybe there would be some kind of purification rite involving Brahmin priests, even though he loathed Brahmin priests.

“That’s fine,” my father said, not even looking up from the paper. I was utterly disappointed at this lack of reaction, this inability to hold the line, so I went and told my mother what I had done. She made a face and said, “Just as long as you don’t bring beef home with you.”

Forty years later, my father is long dead, I am definitely not a Hindu, and I cook beef with relish. I am particularly fond of a steak recipe I learnt from a left-wing Sikh American family in Massachusetts, which involves a juicy ribeye marbled with fat, a distinctly South Asian spice mix, and a cast iron pan. It is tasty, voluptuous in its flavors, so American and yet so Indian, and it happens to be my celebratory meal of choice.

And yet, increasingly, I eat beef with a kind of double consciousness. Where once the meat was all about my rightful rebellion and gastronomic pleasure, it now trails with it other disturbing threads. Beef brings to mind the state of the planet, of a cataclysmic climate change precipitated further by our excessive consumption of meat, in particular beef. In New York, especially, where I am sometimes in the company of white people who are mostly vegan, my beef eating makes me feel like a barbarian, some kind of brown-skinned Trumpist who has shoved his way into polite society.

But beef also reminds me that in today’s India, dominated entirely now by a Hindu-right government led by the prime minister Narendra Modi, eating beef, or possessing it, or desiring to eat it, is a sign of one’s inferiority, evidence that one is not Hindu, not really Indian, and perhaps not even fully human. Beef might be killing the planet, but in India, for reasons that have nothing to do with climate change or a balanced diet, beef can get a human being killed.

• • • •

No item of food has tortured the modern Hindu imagination more than beef. In a belief system where all meat and fish tends towards the unclean and the impure, beef is the ur-meat, a toxic Kryptonite whose sole purpose appears to be the humiliation of Hindus and the downfall of India. Unlike pork for observant Muslims or Jews, beef is not the unclean byproduct of an unclean animal. Instead, for the believing Hindu, it is material evidence of desecration of the most sacred of animals, the cow. Because the cow is the symbolic mother of Hindus, an eater of beef is the eater of Hindu mothers. When I ate that beef sandwich at school, I was eating someone’s mother.

There are numerous strands of belief and history packed into this attitude, complex and sometimes contradictory. It involves a shift from nomadic cattle rearing to more settled agrarian practices; inter-religious disputes and the struggle for power between Hinduism and Buddhism; the depredations of western colonialism and the reactionary Hindu nationalism it spawned; modern notions of masculinity and health; and, finally, the disturbing, present-day relationship between demagoguery and the politics of spectacle.

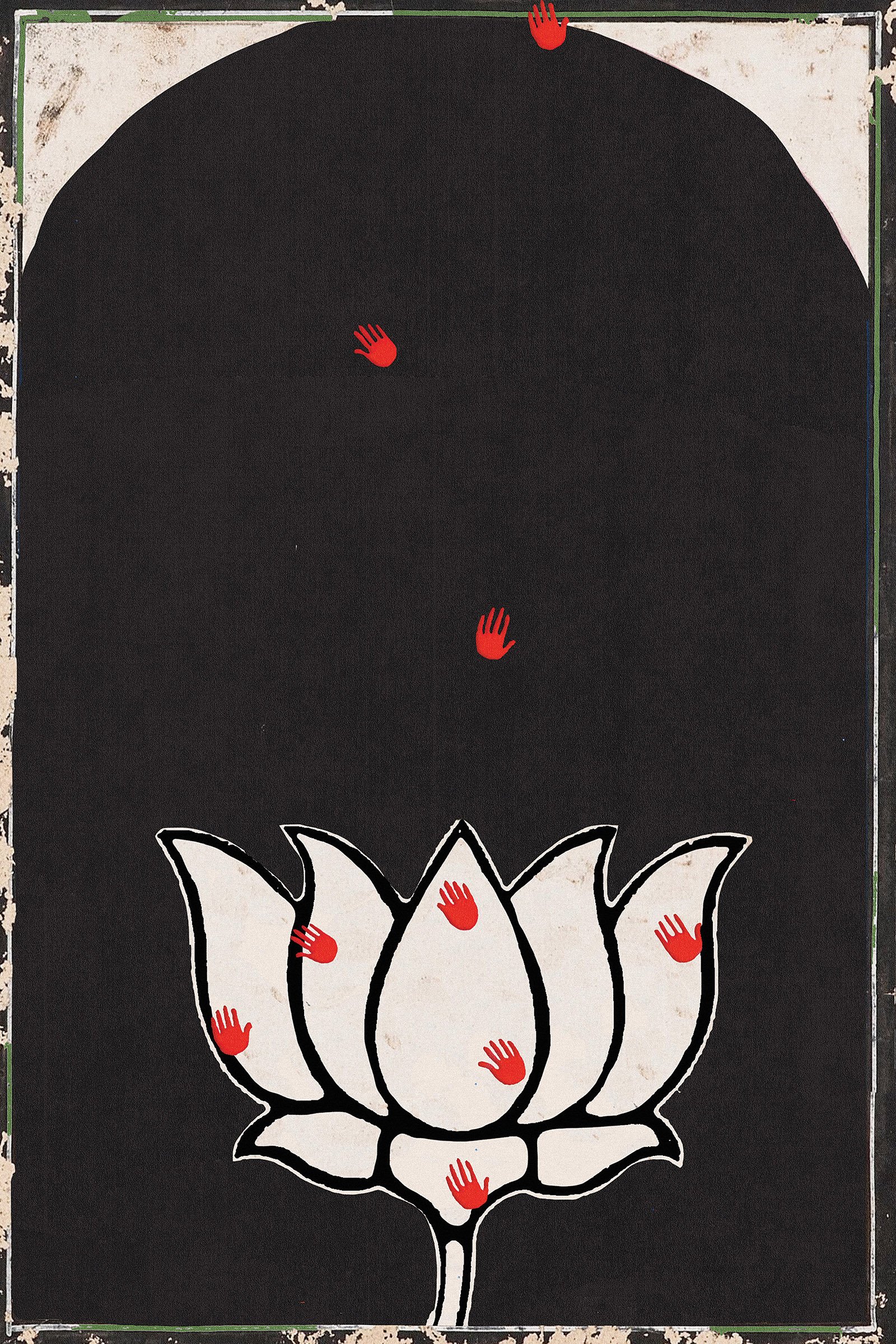

But in contemporary India, controlled by the Hindu right, all such complexities disappear into fundamental, irreducible truths enforced by government fiat as well as by vigilante violence. In 2014, Modi, contesting the national elections, assailed his political opponents as the culprits behind a phenomenon he called the “Pink Revolution.” Speaking to adoring crowds that would eventually hand him a decisive electoral victory and his first prime ministerial term, he elaborated on this phrase he had conjured out of nothing:

Across the countryside, our animals are getting slaughtered. Our livestock is getting stolen from our villages and taken to Bangladesh. Across India too, there are massive slaughterhouses in operation. And that’s not all. The Delhi sarkar will not give out subsidies to farmers… keeping cows but will give out subsidies to people who slaughter cows, who slaughter animals, who are destroying our rivers of milk…

A year after these speeches, with Modi firmly ensconced on the throne, a group of Hindu men broke into the house of Mohammad Akhlaq, a 52-year-old Muslim ironworker in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Akhlaq and his 22-year-old son were dragged out of their house even as a public address system at a nearby temple summoned others to join the mob. Accused of having beef in their refrigerator, Akhlaq and his son were beaten so badly that Akhlaq died of his injuries. The “beef” discovered in his house was sent for “forensic” testing—it turned out to be mutton.

Akhlaq’s death was only among the most visible of the “beef lynchings” that have proliferated in Modi’s India. In Jharkand, in eastern India, two Muslim men transporting buffaloes were beaten to death, their bodies left hanging from a tree. In Rajasthan, on the border with Delhi, a 55-year-old Muslim dairy farmer was lynched in spite of papers showing that he had purchased the cattle with him for milk production. The killings carry the air of spontaneity and unpredictability, and yet the patterns are not hard to read. They manifest Modi’s dog whistles, the victims almost always accused of stealing cattle, even if they indisputably own them, just as they are charged with transporting them for slaughter no matter the evidence to the contrary. In the case of Akhlaq, or of other victims, they did not even need to be in possession of beef. It was enough that they were people who might, in the right circumstances, eat beef.

The majority of victims are Muslims, although Dalits, at the bottom of the caste order and often tasked with disposing of animal carcasses and working with leather, are also brutalized, as was the case in 2016 when four men in Modi’s home state of Gujarat were tied to a car and beaten with iron rods over suspicions of cow slaughter. Although some of the lynchings can be attributed to mobs instigated by Hindu-right political leaders, and some to animal rights groups also led by members of the Hindu right, they are increasingly carried out by so-called cow protection groups that have proliferated in states ruled by the Hindu right. These groups can have as many as 5,000 members, with 200 of them estimated to exist just in and around Delhi.

The killings are often filmed on smartphones by the perpetrators and distributed widely on social media, an indication of their confidence that the law as well as much of Indian society is with them. Between 2015 and 2018, Human Rights Watch recorded at least 44 people killed in “cow-related violence” across 12 states. More recent data is hard to find because the National Crimes Record Bureau stopped collecting information on lynchings and hate crimes after 2017, apparently because Modi’s government considered the data collected to be “unreliable.”

A few months ago, a friend of mine sent me a news clip. He and his television crew had been filming a cow protection gang in the state of Haryana. It is late at night, electric lights reflecting off the rain-washed asphalt at a toll gate. The men in the gang are young and loutish, dressed in tracksuits and sneakers as they stop trucks and clamber on to check for cattle. There is a performative aspect to it, in their chants about victory to the mother cow—“Gau Mata ki jai”— for the camera, and in the gang leader’s soundbites as he talks about his willingness to kill and be killed in his cause. He is a handsome man, aware of his charisma as he smiles and waves, a minor politician or actor taking in the adulation of observers. But all this changes when they find a truck with cattle. The two Muslim men driving the truck are pulled out, and as the vigilantes shout, “Don’t film this,” one of the drivers is hit in the face with a glass bottle.

I couldn’t watch the clip beyond this point the first time I played it. When I went back to it later, I saw how the scene perfectly captured the breakdown of a society and its race towards some apocalyptic, Mad Max future. Brightly painted long-distance buses, their windows curtained, accelerate out of the toll gate. One of the gang members is calling someone, possibly a higher-up in the chain of command. Some of the others are filming the assault with their phones. Everything is happening on the Delhi-Haryana border, a short distance from the parliament, where in September, Modi would present a spruced-up India to President Joe, British prime minister Rishi Sunak, and assorted leaders of the democratic world. The drivers are small, slight men, pleading that they are taking the cows not to a slaughterhouse but to a dairy farm. “Dairy, dairy,” they cry out in English. “Don’t film this,” the leader repeats, but his manner is unflustered, unworried. There have been police vans parked at the scene for quite some time.

• • • •

At eighteen, I found myself in Calcutta (now Kolkata), a city far from Shillong. I was studying at an elite, state-run college. The fee, heavily subsidized, was only fifteen rupees a month, and I had a cheap room in a nearby hostel. But my situation was precarious in other ways. I had moved my parents out of Shillong, engulfed by riots, to another town in the neighboring state of Assam. My father, now retired, was paralyzed from a recent stroke, and my mother, who had never studied beyond high school and never had a job, was struggling to take care of him while living in a town that flooded every summer.

Little money came from my parents during that first year in college. The food at the hostel was rudimentary. When the rice arrived, we spent the first few minutes picking out stones—added by dealers to increase the weight—and making little piles of rubble next to the plates. If I was late for dinner, which was often—I spent the evenings visiting my uncles, trying to convince them to let my parents sell the house they were living in and move to Calcutta—I ate with my feet up on the bench. Massive bandicoot rats, or “pig-rats,” roamed the dining hall floor in search of scraps. Meat was served once a week, two tiny pieces of chicken distributed with infinitesimal precision. If you received a bowl where one piece was a third of a drumstick, and therefore offered more flesh than average, the other piece was a slice of the chicken’s stringy neck.

My weight dropped to a hundred pounds. My clothes were suddenly much too large for me. I woke up thinking about food and waited, with quiet desperation, for invitations to the houses of rich classmates. It was beef that saved me.

Street food in Calcutta was plentiful, tasty, and cheap, but it was still too expensive for me. But near the college was Kalabagan, a poor Muslim neighborhood, ghettoized in the manner of minority neighborhoods in most Indian cities. I could get beef kebabs there for a rupee a skewer, served with a paratha and a side of sliced onions. I ate with people unlike me, working-class Muslim men exhausted from long, unyielding days of backbreaking labor, one of them arguing with me about Salman Rushdie because he planned to demonstrate in front of the British embassy against the publication of The Satanic Verses.

Eventually, I managed to move my parents to an apartment on the outskirts of Calcutta, and I could eat at home. But two years after this move, my father died, our lack of connections to the right people being as fatal to his recovery as our limited resources. My father’s death, sudden and unexpected despite our knowledge that there was no hope of finding good medical care, left me numb. The guilt that had gnawed at me since I was seventeen—when he had been paralyzed and I had turned my back on an engineering degree and had chosen, instead, to study literature—came back with a vengeance. We had struggled financially even when he was alive. Now we would have to survive on my mother’s “widow pension,” which the government had calculated to be a third of what my father had received when he was alive.

I had not meaningfully looked back at the question of my Hindu ancestry since that day at school years earlier. Around me, the Hindu right was stirring into menacing wakefulness, demonstrating across the country to build a temple to the god Ram on the site of a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh. But my father’s death and the accompanying rituals brought the question of faith and belonging back in a sudden rush.

“The prohibition against beef has been followed by legislation that now classifies buffalo—of no particular sacred status to observant Hindus—as cattle, along with camels.”

There was no money to pay for his cremation and kindly strangers and relatives had to help out. My head was shaved on the banks of the Hooghly River where just a few minutes before I had submerged the pot with my father’s ashes. A priest was summoned to our tiny, mildew-streaked apartment to have me go through the final rites. He chanted in Sanskrit, which I did not understand, and tied little rings made of bamboo on my fingers. I think he said they were meant to represent arrows, but I simply may not have understood what he was saying.

I took on the ritual mourning with a cold dedication, thirty days during which I would live as much like an ascetic as possible. I wore two pieces of unstitched cloth and cooked my own meals, rudimentary vegetarian food without spices, onions, or garlic. I did not shave and did not sit on chairs. I felt like a warrior monk, and my guilt and grief and anger hardened into beautiful, sinewy shape. Strangers on the streets looked at me with pity. But for the first time in my life, they also looked at me with respect, and, for the first time in my life, I felt like a Hindu.

As the days went by, though, that feeling faded into the more familiar sensations of rage and hunger. The ritual observations made increasingly less sense, a fantasy against the pressing reality. How was it that only Brahmins were priests, and that the Brahmin man next door was also a gangster? How would my mother and I get by on her widow’s pension? Why was she required to be a vegetarian for the rest of her life? What about the man at the crematorium, the one who had sifted through the hot ash to hand me my father’s remains: Why was that his role in life and why was it determined entirely by the caste he had been born into?

My rage bubbled back, along with a dizziness from days of semi-starvation. I was engaged in a battle for survival, I understood, and I saw no sense in battling by someone else’s absurd rules, on behalf of an identity I did not believe in. I put away my ascetic garments and dressed in regular clothes. Then I went out to eat.

I chose a Muslim restaurant near Central Avenue and ordered beef rezala, a mild, flavorful stew. The waiter was middle-aged and looked shocked. He could tell from my shaved head that I was a Hindu and in mourning.

“How can you do this?” he said. “How can you dishonor your ancestors in this way?” I ignored him. “You should not be eating beef. You should not be here. It is important to respect those who have passed,” he said.

When he came back with my food, he slammed it down on the table without looking at me.

• • • •

Beef has not always been inimical to the Hindu tradition. D. N. Jha, a Delhi university historian, writes that the current iconic status of the cow and the accompanying proscription against beef would have made little sense to the ancestors of present-day Hindus, the horse-riding, cattle-rearing pastoralists who most likely arrived from Central Asia between the 2nd and 1st century BCE and gave rise to the central texts and tenets of what is today called Hinduism. The current, widespread assumption that beef eating was foreign to the subcontinent until it was introduced by Muslim invaders in the 12th century is incorrect, Jha insists, basing his arguments on the textual details available in early Vedic texts as well as copious archaeological evidence, including the presence of “cattle bone fragments” that are “either charred or bear definite cut marks, which suggests that these animals were cooked and eaten.”

Not only were the ancient Hindus of the Vedic Age no strangers to the pleasures of beef, but the now-prohibited meat once had an important position in the hierarchy of offerings made to Hindu gods. “There was not much variation in the menu for Rgvedic gods,” Jha writes in Holy Cow: Beef in Indian Dietary Traditions. “Milk, butter, barley, oxen, goats and sheep were their usual food, though some of them had apparently their preferences. Indra, for example, had a special liking for bulls and the guardian of the roads, Pūsan, devoid of teeth, ate mush.” But animals, including cattle, were killed not just in public sacrifices, but also in “ordinary and domestic rites of daily life.”

When Jha published a chapter from the book online in 2001, he began to receive death threats. Just three years earlier, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had triumphed for the first time in national politics, riding to power on a wave of anti-Muslim violence and rhetoric that often highlighted the protection of “cows and cow-progeny” and the prohibition of beef. As Jha was correcting the final proofs of his book, the original publisher withdrew. When it was eventually released by another, smaller press, Hindu priests held demonstrations against the book, describing Jha as part of “anti-national forces trying to destroy Indian culture and tradition.” Groups loyal to the BJP demanded Jha’s arrest and a ban on the book, and religious and animal-rights groups filed petitions against it. A court in the southern city of Hyderabad ordered the publisher to desist from printing, publishing, and releasing the book anywhere in India until further hearings were held. As a result, Jha told me when I interviewed him at the time (he died in 2021), the book was “for all intents and purposes banned.”

B. R. Ambedkar, the independence-era Dalit leader who was the architect of the Indian constitution and whose rejection of Hinduism’s oppressive caste practices led him to convert to Buddhism, had pointed out in the early 20th century that Hinduism’s aversion to meat, especially beef, was an attempt to recover the political power ceded to Buddhism. Buddhism, which emerged in the Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE, had become immensely popular; by the 3rd century BCE, it had been adopted as a state religion by the emperor Ashoka. “Without becoming vegetarian the Brahmins could not have recovered the ground they had lost,” Ambedkar wrote in Untouchability in 1948. In doing so, he argued, Hinduism cast those who ate beef beyond the pale. “[T]hose who eat the dead cow are tainted with Untouchability and no others,” he wrote.

Jha too points out that the rise of Buddhism and Jainism, with their unequivocal rejection of animal sacrifice and deliberate injury to animals, posed a threat to the Brahmin priestly hierarchy. This, as well as an accompanying shift from pastoralist practices to more settled agriculture, led to Hinduism’s adoption of vegetarianism, he argues. Yet Hinduism’s condemnation of meat, especially beef, took on a new dimension with the arrival of a new group of beef-eaters: British colonialists. By the late 19th century, cow protection movements had gathered force in India under revivalist Hindu movements, particularly the Arya Samaj in Punjab.

The target of these movements, however, were always Muslims and never the British overlords. Lord Linlithgow, the viceroy of India from 1936 to 1943—when a famine in Bengal killed nearly three million people—liked to be accompanied to dinner by a band playing “The Roast Beef of Old England.” The lyrics go:

When mighty Roast Beef was the Englishman’s food,

It ennobled our veins and enriched our blood.

Our soldiers were brave and our courtiers were good

Oh! the Roast Beef of old England,

And old English Roast Beef!

Linlithgow, needless to say, was never troubled by Hindu revivalists. The majority of them, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the secretive, paramilitary organization founded in the 1920s and for which the BJP serves as a political front, remained profoundly servile to the British while directing their violence at Muslims.

Beef became something new now, a complicated, contradictory marker of being, a necessary condition of nationhood. It offered the pathway to an easy, unifying Hindu identity being fashioned by the Hindu right for people of different castes, languages, gods, and eating habits. It provided a convenient differentiation from Muslims, a demarcating line for who could be a citizen in the new nation being imagined after the departure of the British, and a convenient flashpoint of violence. Riots took place around allegations of cow slaughter and the desecration of temple grounds, while pork was often placed in or near mosques as a provocative counter move.

Yet it was not just Muslims or Dalits who ate beef, but also the British master. Western imperialism, triumphant everywhere, was an empire of beef. This is what allowed the breeding of the American Brahman cattle in the United States in 1885, out of stock imported from India. Today, the breed lives on in the popular Beefmaster cattle, which, one could argue, has been true to India’s Vedic roots in producing Brahmin beef. Iconic figures of the Hindu right, such as Vivekananda, the 19th-century Hindu monk, and Vinayak Savarkar, who, inspired by Italian Fascists and Nazi Germany in the 1930s, envisaged a future India that would be a nation composed entirely of Hindus, occasionally expressed sneaking admiration for the vigorous masculinity produced in world-conquering Westerners by beef.

On the other hand, even people opposed to the Hindu right, like Gandhi, fed the Hindu-right mindset of beef as a marker of savagery. Although opposed to all violence, including against Muslims, Gandhi’s very public vegetarianism reinforced the stereotype of the meat-eater, and especially the beef-eater, as violent and sexually aggressive. Nearly a century later, the stereotype remains.

• • • •

In modern-day, globalized India, the war against beef has taken on a new, fervent form of life beyond lynchings. Beef is banned in 23 out of 29 Indian states. Uttar Pradesh, the largest, poorest, most populous, and possibly most violent state in India, is a leader in cow protection legislation. It prohibits the slaughter of cattle as well as the storing and eating of beef, although it supposedly allows the import of beef “in sealed containers, to be served to foreigners.”

But the lines, inevitably, have expanded, and restrictions have crept into other kinds of meat. India ranked first as a beef exporting nation until 2017, earning around $4 billion a year from the trade, although its beef originated not from cattle but from the curly-horned buffalo indigenous to the country. The slaughterhouses, largely owned by Muslim-owned corporations, are said to be halal and state-of-the-art, the buffaloes themselves raised largely on a free-range diet. But the prohibition against beef has been followed by legislation that now classifies buffalo—of no particular sacred status to observant Hindus—as cattle, along with camels. India’s ranking as a beef-exporting nation has since dropped.

An enforced vegetarianism has, in fact, taken off from the ban on beef, it being increasingly common for shops selling meat of any kind to be forcibly closed during Hindu festivals. On trains, hotels, aircrafts, and workplace cafeterias, it is the norm to serve only vegetarian food, and landlords renting out apartments and houses demand outright that tenants cook only vegetarian food. Sudha Murthy, a self-help author married to the Indian tech billionaire Nandan Nilekani, and the mother-in-law of Rishi Sunak, recently declared on television that she was a “pure vegetarian.” She carries food with her when traveling abroad, she said, and her biggest worry when eating in foreign lands is whether a spoon given to her might have been in contact with non-vegetarian food earlier. Murthy’s worry, like that of most upper-caste vegetarians, is not about hygiene but ritual contamination. If the spoon has touched a beef stew, it is forever dirty, and no number of rinse cycles in the dishwasher will take care of that existential pollution.

This is why in India, restaurants and eating stands blithely advertise themselves, like Murthy, as “pure vegetarian.” The argument made in their defense is that they do so to distinguish themselves from vegetarians who eat onions, garlic, and eggs—food items considered to encourage sexuality and aggression— but the truth is that they place themselves at the top of a sliding scale of impurity. At one end, the pure vegetarians. At the extreme other, falling entirely off the scale, the deep abyss of the beef-eaters—Muslims, Dalits, Christians, Adivasis, and tribals. It is only the Westerner, beef-eating but powerful—Trump, presumably, ate his roast beef as blithely as Lord Linlithgow when bonding with Modi—who has stood outside this equation, but there too, history has turned the way of the Hindu right, with Western perception of all or most Indians as plant-eating yogis reinforcing their vegetarian order. When Vivek Ramaswamy emerged as a Republican presidential candidate this summer, the headlines as well as descriptions in the US press routinely described him as “vegetarian” and a Hindu, the two categories seen tautologically as reaffirming each other.

In truth, between 70 to 80 percent of Indians are not vegetarian, eating eggs, meat, fish, or all of these. Meat consumption is highest amongst Muslims, Dalits, and Adivasis, but even among upper-caste Hindus, over 50 percent are non-vegetarian. Yet the diet of the majority is sparing to the point of deprivation. What Murthy’s pure vegetarianism and Modi’s cow vigilantism covers up is that India is a profoundly unequal society in ways old and new, its eating habits caught between poverty and segregation, between ritual purity that does not preclude poor eating habits and mass-produced, Westernized junk food that guarantees a deficient diet.

Poultry consumption has increased in urban areas in India, chicken being the nation’s most popular meat—chicken biryani was the most frequently ordered item on the food delivery app Swiggy in 2021. Yet fifteen states, the majority with BJP governments, have prohibited eggs from being served in the free school lunch that often serves as the primary meal of the day for poor students. So, on the one hand, there is the prevalence of obesity and diabetes for those who are wealthy, and on the other, the fact that nearly half the children in India under the age of five are underweight and more than half the children and women in the country are anemic. In this climate, enforced vegetarianism and beef vigilantism are absurdities.

“Beef was a treat, a sacrifice from the animal to the human, and one ate it with that knowledge and awareness.”