Even so, the longer I remained in Bulgaria and the region, the more I was haunted by the uncomfortable feeling that a frontier was closing once again. Residual energy from the 1990s still hung in the air, a desire for experimentation still bubbled on the fringes, as the influx of EU capital had not completely smothered creative disorder—the most essential of life conditions—but I could already see clouds gathering somewhere in the distance. A lot of Bulgarians were certainly better off since “the changes,” or at least they could afford to buy more commodities and travel abroad as they wished, but they had become tired, more apathetic, less imaginative, their dreams smaller. Maybe that was the fate of any revolution: after the initial bang, there’s a natural period of calm, a dust-settling. The body can’t always live on the edge, in a whirlwind of adrenalin—it’s much too exhausting. There is a time for everything, as the prophet tells us: a time to scatter stones and a time to gather them, a time to tear and a time to mend, a time for war and a time for peace.

There was an uncomfortable paradox though: the more life organized, the more it settled into a routine; the more affluent and peaceful society became, the better paved the roads and the fancier the cars, the more normal and orderly the days—I suppose the public ideals journalism indirectly fights for—the fewer possibilities glimmered on the horizon. As civilization tamed the wilderness—to use an antiquated and controversial but in this case perhaps not wholly irrelevant metaphor—something intangible was lost: a spirit, perhaps, or an aspiration it’s difficult to put my finger on. For all its numerous faults, the 1990s had sparked one of those utopian visions of building a new world atop the ashes of the old, as Communism had once done.

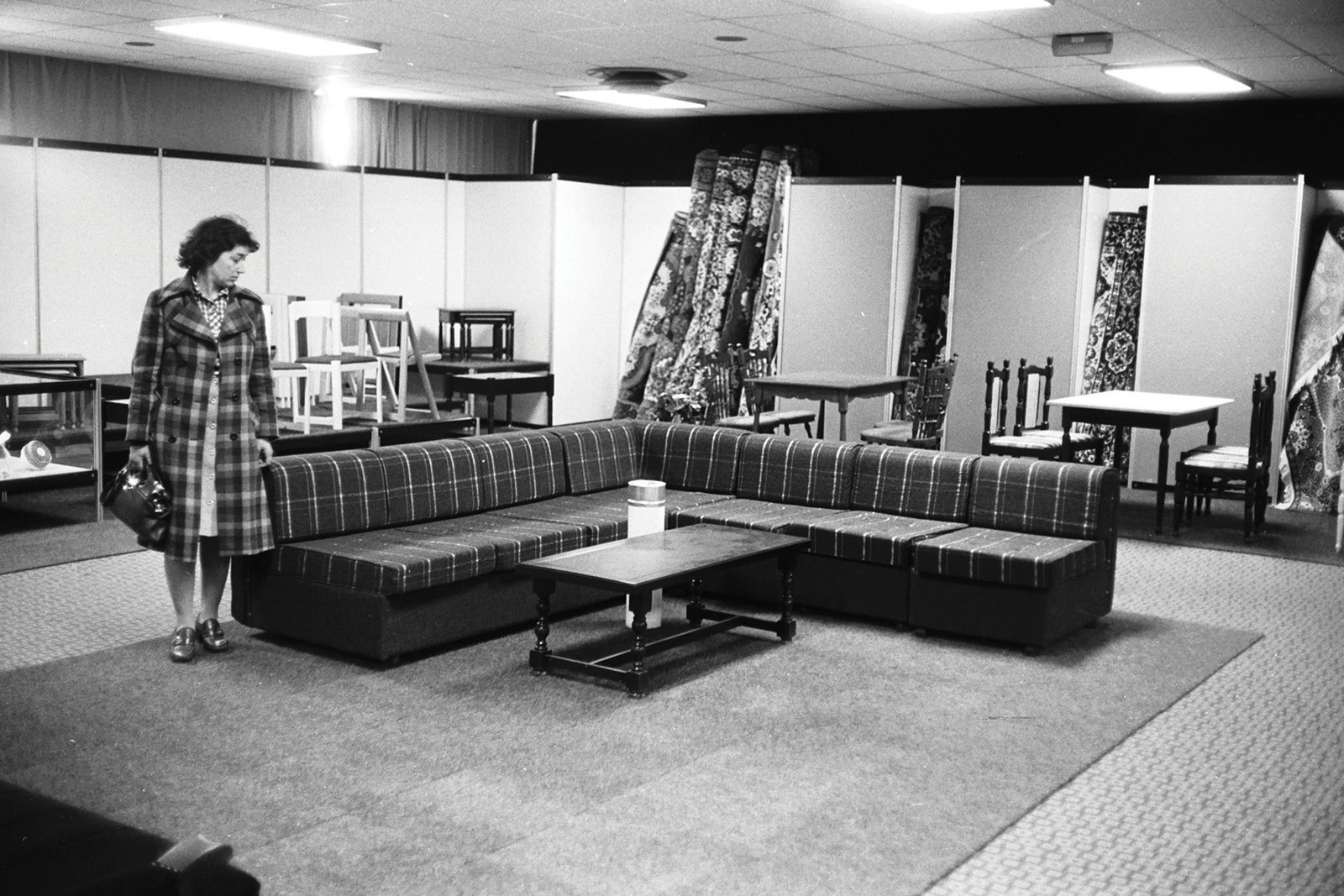

Next came the bureaucratic goal of joining the European Union—“the civilized world,” in the lingo of politicians—which a vast majority of Bulgarians felt enthusiastic about. When that was finally achieved, however, grand, inspirational ideas for the future seemed to gradually peter out. Occasional crises like migration, environmental issues, the need for judicial reform, and the rampant political corruption kept Facebook filled with outrage and the media pundits occupied, but those usually melted into oblivion with the next news cycle. What should Bulgarians strive for next? What should they look forward to? Consumer society offered one solution, of course—a new TV, a new smartphone, a new car, a new apartment—but that could be only a temporary fix, for even the acquisition of new objects grows old in the end.

• • • •

Have I been late again, I often ask myself when I think about my return to Bulgaria a decade ago, the frontier more or less tamed by the time I had arrived? Or is this just the way of the world, the order of things? Or is it my constant craving for novelty and excitement, the specific chemistry of my brain that has distorted my expectations and made me project my unresolved psychological drives onto the social and political canvas? Or is there, indeed, some general malaise that imbues our current moment, a common feeling of a dead end?

It’s a conundrum impossible to resolve. Yet, faced with it, I recall Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, one of the greatest novels on the subject of time. Its protagonist Hans Castorp goes to pay what is supposed to be just a short visit to his ailing cousin at a TB sanatorium in the mountains of Switzerland, but for a variety of reasons (illness, love, love as illness) he ends up staying for seven years. Initially, everything is new to him, so packed with remarkable encounters and incidents, thoughts and impressions, that the duration of time stretches out and each day feels like weeks. As the weeks turn into months and the months into years, however, as his mind becomes habituated to its environment, as routine sets in and morphs into endless repetition, time quickens its pace and blurs to such a degree that its passing becomes almost imperceptible to the senses and, for all intents and purposes, it ceases to exist. And here is Mann himself on the issue:

For the moment we need to recall the swift flight of time—even of a quite considerable period of time—which we spend in bed when we are ill. All the days are nothing but the same day repeating itself—or rather, since it is always the same day, it is incorrect to speak of repetition; a continuous present, an identity, an everlastingness—such words as these would better convey the idea. They bring you your midday broth as they brought it yesterday and will bring it tomorrow; and it comes over you—but whence or how you do not know, it makes you quite giddy to see the broth coming in—that you’re losing a sense of the demarcation of time, that its units are running together, disappearing; and what is being revealed to you as the true content of time is merely a dimensionless present in which they eternally bring you the broth.

Ay, there’s the rub: the broth. Maybe I’m imagining this, but it seems that all of us—in Bulgaria, in the rest of Europe, in the United States—are lying sick in our beds while somebody is bringing us the same broth over and over again. For the closing of frontiers is not simply a spatial issue, but a temporal one as well, as space and time are, of course, interrelated. Like Communism, capitalism is a teleological system at its root, relying on a narrative of progress, on a forward-moving vector of time, but when that time turns cyclical, repetitive, without a clear direction, the system begins to disintegrate, not under the weight of its own contradictions, as Marx would tell us, but under the weight of its own uniformity. The recent coronavirus epidemic, which measured itself in seasons—winter spikes followed by summer lows—only made that condition legible. But social media too, with the essentially cyclical nature of its feeds, with its intermittent flows of information that blur into non-information, has deepened the sensation that one is wasting away in the prison of timelessness. We’re often told that we live in the most dynamic period in human history, where change—political, economic, technological—happens on a nearly daily basis. That is true on the physical level, of course, but the psychological optics are rather different. Like a wheel that spins so fast that its spokes appear stationary or moving backwards even (the so-called wagon-wheel effect), the fast rate of transformation has come to feel like stasis. Hurtling toward a black hole, we seem to be endlessly stuck, horizonless, in the event horizon.